A Fighting Chance for North Coast Bull Kelp

Michael Esgro, OPC Marine Ecosystems Program Manager & Tribal Liaison

As a lifelong Monterey diver, I’ve been devastated to watch California’s once-lush kelp forests turn into “urchin barrens” seemingly overnight. I’ve also been deeply moved by conversations with my north coast diver brethren (both at public meetings in Sacramento and over beers in Noyo Harbor) about the devastating consequences that this ecological collapse has had on the economy, culture, and spirit of California’s north coast, where kelp declines have been the most severe. So when I was offered the chance to observe a new kelp restoration project in Mendocino County – a unique partnership between OPC, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, Reef Check California, and local commercial fishermen – I threw a scuba tank in my truck and drove north without hesitation. And that’s how I found myself pulling on a wetsuit on a foggy Sunday morning, excited for an underwater tour of the Noyo Bay restoration site.

Alongside Tristin McHugh, Reef Check’s North Coast Regional Manager and my divemaster for this excursion, I dropped into the uncommonly clear water and soon came upon Pat and Grant Downie, a father-son team of commercial red sea urchin divers. Using only their hands and specially designed rakes, they were quickly clearing the reef of kelp-eating purple urchin, demonstrating a level of skill and efficiency that comes only with a lifetime of urchin diving. For reference, I participated in a recreational urchin removal event at Noyo Bay last summer, and I was proud of the 5 pounds I surfaced with. The Downies’ haul last Sunday? More than half a ton.

Commercial fisherman Grant Downie removing purple urchin from the reef at Noyo Bay. Photo: Tristin McHugh/Reef Check California

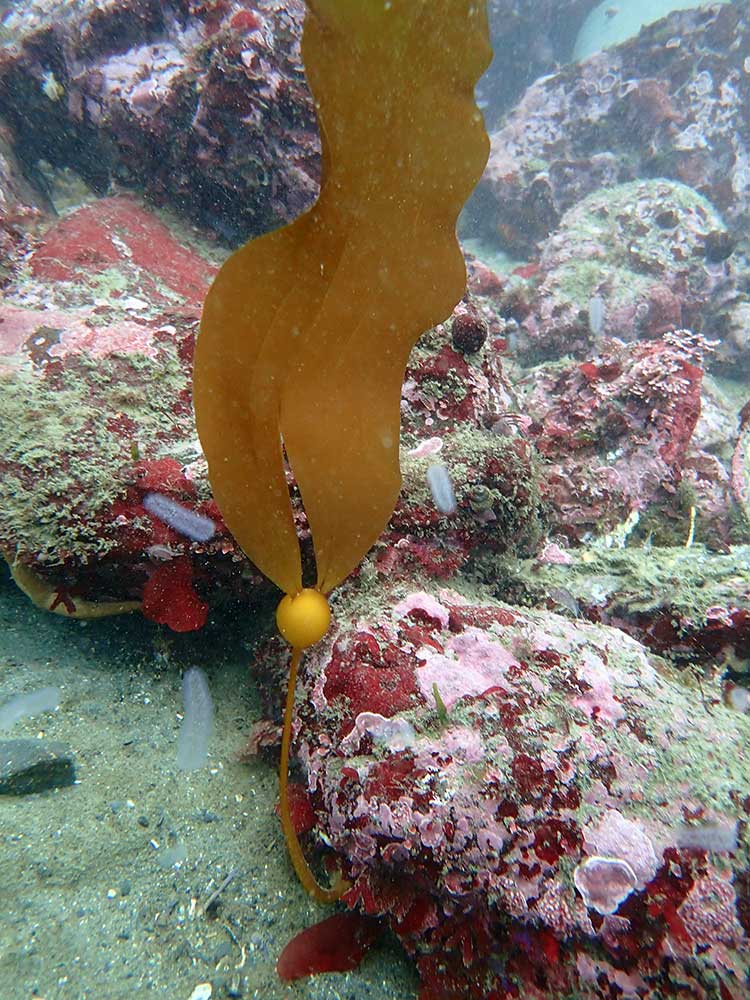

As Tristin and I made our way across the reef, I was impressed to see the progress that has been made since urchin removal operations started only a month ago. When I last saw this site, purple urchins were so dense that the ocean floor looked like a spiky purple carpet. Now, it was bare rock. And about halfway through the dive, I saw something I never thought I’d see at Noyo Bay again – several baby bull kelps growing on the newly cleared reef. I hovered over one for several minutes. This piece of algae was no bigger than my thumb, and it looked like such a fragile thing, especially compared to the towering forests that once stood here. But it also struck me as defiant, evidence of resilience in a changing ocean, new life in an environment that, up until a few weeks ago, seemed beyond redemption.

Back on the dock, as we watched divers hauling in basket after basket of purple urchin, I talked with colleagues about the sighting, and all of us (ecologists to the core) agreed we can’t yet say that urchin removal is directly responsible for kelp regrowth at Noyo Bay. That requires more data, and replication, and comparison with unmanipulated reference sites. In fact, it’s the central scientific question that we are trying to answer with this project. The image of that baby bull kelp stayed with me, though, as I drove home down Highway 1 and looked out at a coast that was once lined with thick brown tangles. We’re nowhere near the end of the story. But at a couple of spots in Mendocino County, we’re at least giving kelp a fighting chance.

Landed purple urchins ready for processing and data collection. Photo: Mike Esgro/Ocean Protection Council

Dive team enjoying uncommonly clear and blue conditions at Noyo Bay last weekend. Photo: Tristin McHugh/Reef Check California